Mars Curiosity – formerly the Mars Science Laboratory – has been exploring the Red Planet since August 2012 after launching in November 2011.

It’s the size of a Mini Cooper and about twice as large – at 2.9m long, 2.7m wide and 2.2m tall – as the Spirit and Opportunity rovers which landed in 2004.

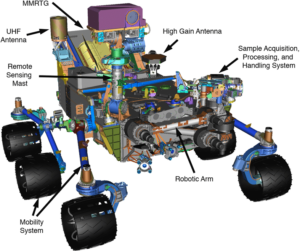

Curiosity has six chunky electric wheels, a robotic arm to probe the Martian rocks and soil, a camera mast to give it an all-round high-definition view and antennas to communicate with Earth. It can talk to Earth directly, but mostly it uses a high-speed relay through three orbiters launched by Nasa and Europe since 2001.

Its tools include an infrared laser to vaporize rocks – a special camera analyses the chemicals released – and a drill to collect samples from inside rocks and under the soil for microscopes and other instruments on board to test.

Solar panels just can’t provide the sort of grunt this laser-armed robo-tank demands, so it is equipped with a nuclear power source.

Risky? Not really. It’s not a nuclear reactor, just a chunk of radioactive material which gives off enough heat to create electricity for a bank of mobile phone-style lithium ion batteries. The 4.8kg of plutonium should be good for at least 14 years of operation if summer dust storms, winter cold below -100C and solar radiation don’t wear out the rest of Curiosity’s components first.

Since 2012, Curiosity has sent back more than 200,000 photos of the alien terrain, and scientists at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Lab have used these to create a 3D model of Mars.

This has been developed into a piece of software called Access Mars which allows you to explore the terrain of Mars, gives you scientific information from Nasa’s team and find out where Curiosity took a selfie.

Curiosity has found evidence that Mars could have supported life millions of years ago, when a thicker atmosphere supported liquid water, and there are abundant chemicals in the soil to build and feed the microbes. There have even been hints of basic organic chemicals, the building blocks of life as we know it.

There’s also lots of water trapped in the soil, which is good news for future manned missions which could use it for fuel as well as for keeping astronauts and their crops alive.

Mars probes don’t move very fast – the operators on Earth pick a target, plan a route and Curiosity slowly makes its way across the ground. When it reaches a target, they’ll investigate it until they’ve seen all they can, then it moves on to its next target.

You can normally find Curiosity’s latest location at the Nasa Mars Science Laboratory site.

Would you like to share your thoughts?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *