Gobekli Tepe, Turkey (11,000–9,000 BCE)

In Turkey, the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers define an area that has come to be known as The Fertile Crescent. In this area lies the (thus far) oldest discovered evidence of human habitation. There are many sites in the Fertile Crescent begging to be explored, but one stands out among them, and indeed, among all of the historical sites on the planet. Gobekli Tepe is considered to be one of the first temples in the world, predating Stonehenge by about 6,000 years — its history dates back to the 10th millennium BCE, or approximately 11,500 years ago. The site was abandoned after the pre-pottery neolithic era, or about the 8th millennium BCE.

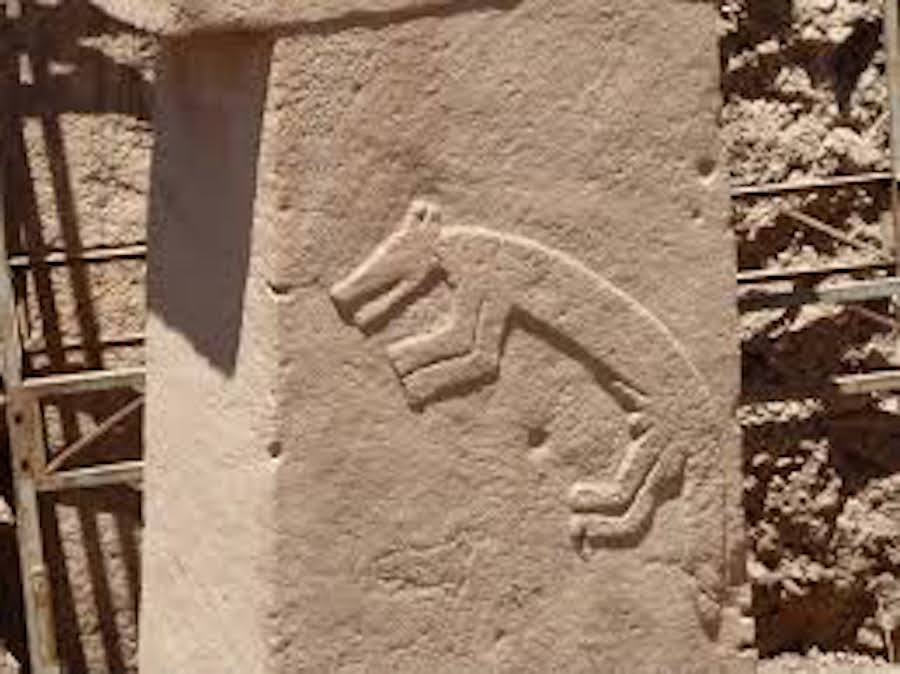

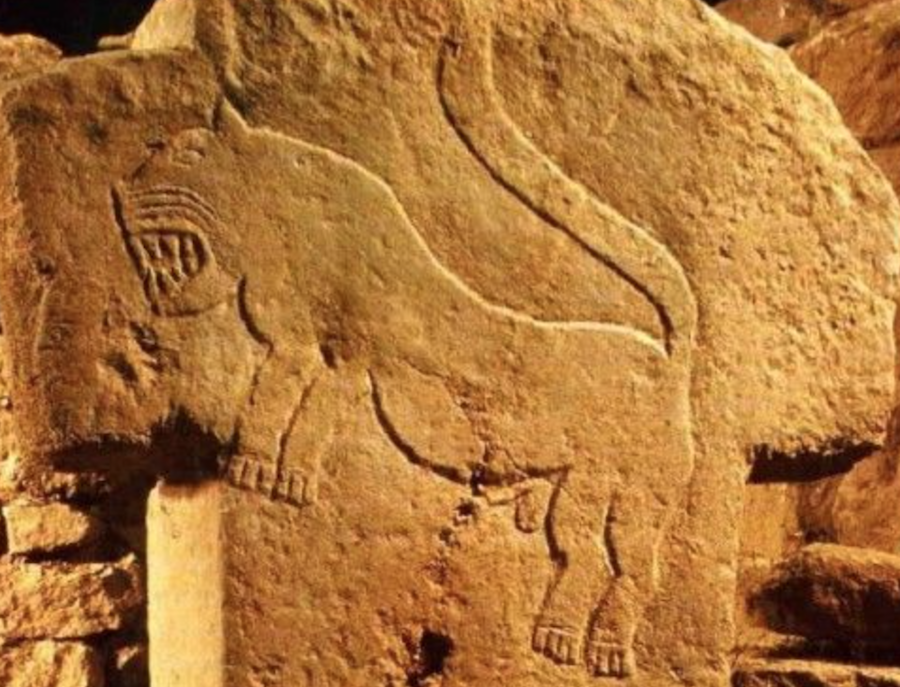

The site spans some 300 meters breadth on a hilltop about 30 miles north of the Syrian border. The site so far is comprised of some 200 pillars in 20 circular / oval structures, scattered around three primary, center stone constructions. Each structure consists of ‘T’ shaped pillars, up to six meters in length, and weighing 20-60 tons each. Strangely, the center stones of these three primary circles seem to form a perfect equilateral triangle, raising more questions than are answered. The pillars are adorned with carved reliefs of various animals such as foxes, ducks, and wild boars, among others.

The site dates to a time when people were in transition from hunter-gatherers to farmers. The people of Gobekli Tepe had apparently not yet domesticated plants or animals, but settled in the area and used what resources they found around them. I appears that over many thousands of years, the culture moved toward the area

Although the site is currently only about 10% excavated, it is already giving up hints about the culture that created it. Archeologists believe that the site was a religious site, and not regularly inhabited, as it seems there was no ready supply of water necessary to sustain life. Perhaps it was a pilgrimage destination. And evidence suggests that it was maintained and modified over many generations. Based on carvings and bone remnants, it is presumed to have been a site for rituals, likely honoring recently deceased family members or commemorating dead chiefs or other tribe members.

Its discoverer was a local farmer, who noticed a stone projecting out of the earth, and upon examination, it became apparent that the stone contained engraved figures. A German archeologist, Klaus Schmidt, was the first to excavate it in the mid-1990s. He is responsible for much of the information that we have gleaned from the site. He died in 2014, but the work has continued, with still much for us to learn.

Would you like to share your thoughts?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *